Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

The storytelling strategies of Celeste help the player to identify closely with the protagonist. Celeste crafts an emotionally sensitive gaming experience, encouraging the player to fail and learn from their mistakes in order to reach the top of the mountain.

The 3D level select screen sets the scene for the 2D pixelated platform game play, helping to emotionally center the player before we start fighting on the protagonists behalf. In Adrienne Shaw’s Gaming at the Edge, she notes that “identification, according to interviewees, occurred largely through the narrative, non-medium-specific aspects of games rather than through their interactivity” (101). Celeste successfully builds a heartfelt narrative through the 3D screens that push the narrative forward, bookending the 2D platformer levels. Another detail that pushes identification forward in Celeste is the fact that the game also lets you name the protagonist. I chose to name her my own name, which I think subconsciously lead me to put myself in her shoes even though I was observing her from a third person perspective.

The mechanics also get you emotionally invested in the story, empowering you to overcome even the trickiest obstacles that game hurls at you. Everything in the game looks impossible before you’re slowly introduced to new mechanics that allow you to overcome your limitations, acting as a tidy metaphor for overcoming human struggle, something everyone can relate to on an emotional level. The platforms look unmanageably difficult as you get further and further into the game. For instance, the introduction of the spiky, icy walls makes it seem as though you have no chance. But the game introduces the dash mechanic, which allows the player to accomplish the seemingly impossible. When you die, the game speedily places you right back to where you were at the start of the current platform. It encourages you to fail, die hundreds of times, and learn from your mistakes without punishing you for the process. It motivates you to keep going and persevere through the trickiness in order to reach your goal by feeding you bits of story in between the platforms you move through.

Celeste elevates the basic platformer format that we all know and love to something truly special—an emotional experience that, by the end, affected me greatly. I felt so invested in the story and what would happen next, and I would attribute that investment largely to the skillfully employed storytelling strategies. Giving us little bits of story at a time, rather than all at once, made me want to keep playing and wish for it to never end.

Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture by Adrienne Shaw

The aesthetics and game sound of “Journey” contribute to the overall visual metaphor that is the game itself. My interpretation of the game is that the figure’s traversal through the environment is a metaphor for a human’s walk through life itself, with the conclusion of the game correlating to death. Niedenthal explains that gaming aesthetics refer partly to “the sensory phenomena that the player encounters in the game” such as its “visual, aural, haptic, embodied” traits (2). “Journey’s” visual aesthetic is rich in color, allowing the player to be swept up in its dream-like world. It’s hard to fathom any world outside of this one when you’re playing it, contributing to the life-itself metaphor. The soft sounds are also spellbinding and almost ASMR-like in nature. We hear the soft sand shifting as the figure moves forward, and the squeaking of the little rugs that lift us up and help us along the way. The controller vibrates softly in your hand as you jump, never too aggressively. The whole thing causes a lull to work over you as a player, sweeping you up into its fantasy. It’s not a fast-paced game, and that’s definitely by design. It wants you to take time and savor the environment and aesthetics that surround you. In Karen Collins’ writing on Game Sound, she expounds on the differing levels of interactivity with sound in games, stating that “audio can serve a wide variety of functions” in games (127) . The music is definitely the most important sound that occurs in Journey, with interactive sound taking somewhat of a back seat. The function of the music in Journey is all enveloping the game player and establishing a rich tonal landscape. Austin Wintory’s score also often dictates subtle or more overt changes in mood as you progress further through the game.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Game Aesthetics by Simon Niedenthal

Game Sound, An Introduction to The History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design by Karen Collins

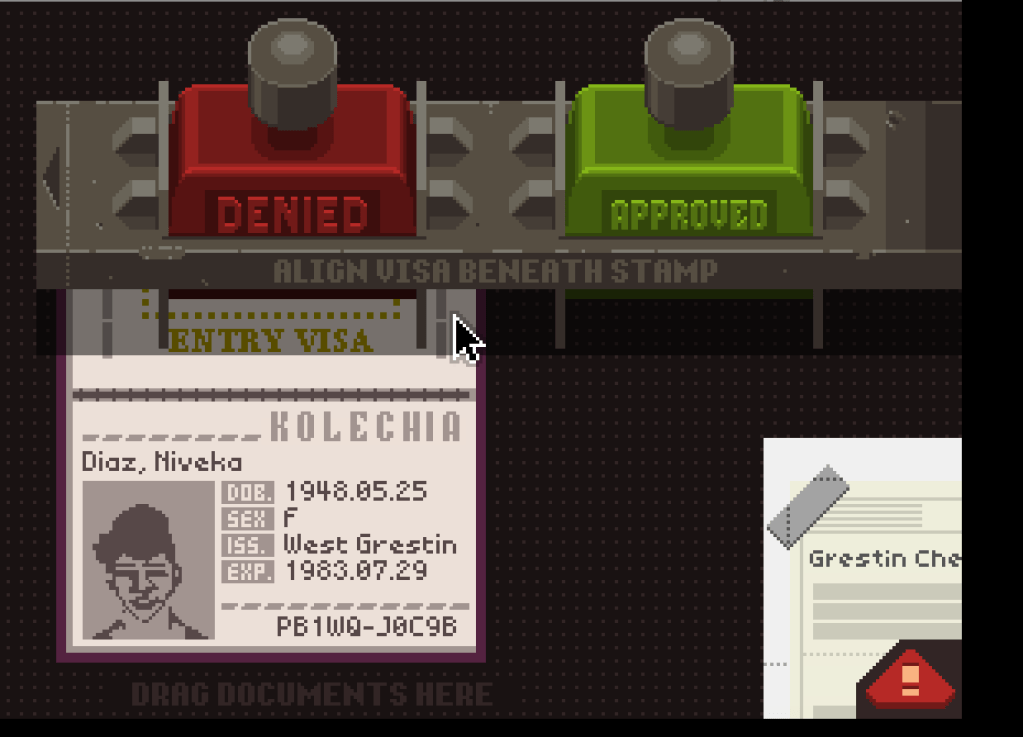

Papers Please is an unusual game. It’s repetitive, its graphics are rather basic and unflashy, and there is a very minimal narrative stringing you along as a player. Despite its offbeat nature, Papers Please still general conforms to most of the tenants of play outlined by Huizinga in the reading. There’s something about it that keeps you wanting to play more.

Huizinga argues that one of the most fundamental elements of play is that it’s “not of the ordinary world, yet very much tied to the everyday” (Huizinga 98). Papers Please perhaps exemplifies this tenant to the most literal degree in that it makes the monotony of a work day into a playable, voluntary, enjoyable playing experience for the average gamer.

Huizinga stated that play should offer a different, special, and unique experience to the player. Though the activity of stamping papers in Papers Please is rather quotidian, the context of that activity is what heightens it to the experience of play. The game creates a fictional country, with fictional surrounding regions, for you to defend and embody as a national officer. The player gets to play pretend in this role, and in this fantasy country, even though the circumstances are not particularly fantastical. It fits this element outlined by Huizinga perfectly, but it does not conform exactly to the way Huizinga theorized about play.

Even though play is thought to exist outside of ordinary life, we as gamers might choose to play a game about a work day because it gives us a sense of control and reason, where in life we have none of that. A typical work day might often leave the average worker feeling unheard, frustrated, and out of control. You might feel under the thumb of an incoherent boss, or like you are swamped with tasks that should be given to your subordinates. A game like Papers Please gives you a work day perfectly, blissfully run. You are in control. It’s a rational, reasonable world despite its fiction, and there’s something inherently comforting about that to a player. Additionally, we might want to replicate a work day that is totally outside of the work day that we live in our own lives. Even though Papers Please shows a normal work day, it shows a work day that is likely quite different from what most of us experience. It might feel counterintuitive, but my own anecdotal experience proves it to be true: It’s fun to work… as long as it’s on your own terms.

Rouse, Richard, et al. Game Design: Theory and Practice. Wordware Publishing Incorporated, 2005.

Donkey Kong is an ideal arcade game according to the parameters defined in Richard Rouse’s “Game Analysis: Centipede” piece. You play as Mario, traversing different linear platforms, avoiding the obstacles being thrown at you by Donkey Kong as you make your way to Princess Peach. Your controls are fairly limited here, and the game relies largely on your timing as a player. As a new gamer in general, this was definitely a challenge! After 30 minutes of play, I still wasn’t able to get past the first platform. The one “defense” you have against the onslaught of obstacles being tossed your way is a hammer. The first thing that stands out to me about this game is the infinite play feature. Rouse says that “having an unwinnable game makes every game a defeat for the player (463)” which felt apparent to me as someone new to the game, and arcade games in general. I have very little experience with games, but this was one of the more aggravating gaming experiences that I’ve had, due to this “unwinnable” nature that Rouse comments on. I think it’s very likely that the infinite play is more fun in a social environment like an arcade with a crowd of friends surrounding you. At home, losing over and over just makes you want to turn the game off. There’s an inherent dissatisfaction with the game experience. Knowing that there’s no real way to win makes the gaming experience sort of sadistically amusing, but only up to a point. Put simply: I found it fun, until I didn’t! It’s possible that the emulator might drag the playing experience down a bit, too. The game allows you to score points after clearing hurdles and avoiding certain obstacles, which Rouse references as one of the most important elements to a successful arcade game. You’re rewarded for getting better at the game, which does encourage the player to keep playing. Rouse argues that classic arcade games should have no story, which this game adheres to. Narratively speaking, it’s incredibly simplistic: advance up the platforms to beat Donkey Kong and win Princess Peach back from his clutches. The narrative never progresses beyond this basic set up, and never requires the gamer to engage with new elements of world building, or new characters. Players of the game might be bringing outside knowledge of the Nintendo universe, which could very well add to the narrative experience of the game, but none of that is baked into the gaming experience on its own in Donkey Kong.

Rouse, Richard, et al. Game Design: Theory and Practice. Wordware, 2005.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.